The Muse Inks

Beauty on Borrowed Time: "The Substance" (2024), Internalized Beauty Standards, and Cosmetic Procedures in Today's Feminism

by Gabrielle Lopez

May 22, 2025

Content Warning: This article may contain plot spoilers. Reader discretion is advised.

Why are we so against growing old—looking old?

The moment a gray strand of hair shows itself, we pluck it out. We invest in various skincare products to prevent the wrinkles from creasing our skin, from marking our ages right on our faces for everybody to see.

Maybe I shouldn’t presume to know what I’m talking about. Maybe if I were to say that wrinkles, freckles, papery skin, and laugh lines are beautiful, I might come off as romanticizing. What do I know? After all, I’m still in my twenties.

But all people succumb to change, don’t we? Everything creases and crumples, fades and withers. Why do we think that this natural state of things makes us any less beautiful?

Of course, when we think of beauty, we think of someone young. Snow White wasn’t old when she was targeted for being the fairest. In fact, the fairy tale completely skips over the older queen in favor of Snow White.

In Pursuit of Beauty

Our beauty seems to hinge on borrowed time—or maybe it just seems so because we think that once we’ve crossed the threshold into a certain age, we are no longer beautiful. So not only do we weed out the stray strands of gray hair, but once they’ve become “too much”, we have our hair dyed back to its youthful color. Once skincare no longer proves to be enough to stop the wrinkles and other flaws from shining through, we have our faces—our entire bodies, even—completely altered to look young, to look “better”, to look beautiful again, as if we’d already stopped.

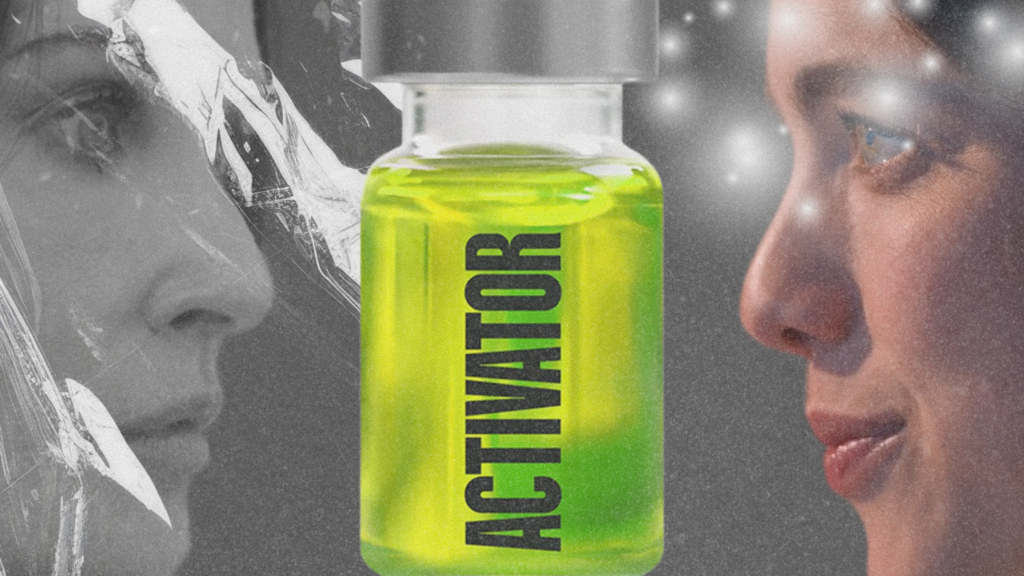

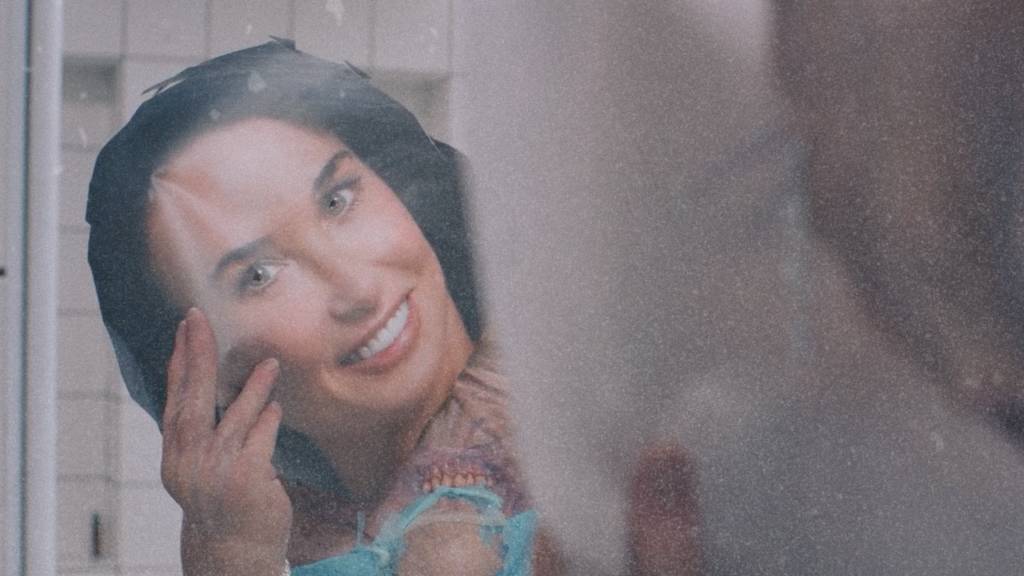

Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) and Sue (Margaret Qualley) looking at themselves in the mirror in “The Substance” (Fargeat, 2024)

Around the world, millions of people undergo varying types of cosmetic surgeries and other non-surgical aesthetic procedures annually. The market size for such has already reached nearly a hundred billion dollars in 2024 and is only bound to double by 2033. (Research and Markets, 2025)

Our beauty seems to hinge on borrowed time—or maybe it just seems so because we think that once we’ve crossed the threshold into a certain age, we are no longer beautiful.

People aged 40-54 make up a whole third of people undergoing cosmetic surgeries annually in the United States alone, while those aged above 55 are no exception from the trend. Facelifts, Botox, liposuction, breast augmentation, eyelid surgery, and skin tightening are common procedures that people in the said age range opt for. (Statista Research Department, 2025; Zochowski Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, n.d.)

Cosmetic Procedures through a Feminist Lens, the Female Gaze in “The Substance”

Perhaps the point of today’s feminism is that we all have a choice now, a chance, a say in our personal and political matters. So if a woman chooses to have her body altered, then so be it. As long as she feels empowered, her confidence is boosted, and she feels good about herself, then it’s okay. It’s her choice, after all.

But more than the result of such changes, what about what made her feel lacking in the first place? The impossibly high standards that made her resort to having parts of herself removed?

“The Substance”, an Academy Award-Nominee for Best Picture in 2024 directed by Coralie Fargeat, asks these questions and leaves viewers reeling from what it shows of our reality, our experiences of beauty. Satire, horror, and sci-fi, the film especially tackles the nuances of beauty—particularly the traditional standards for it—as the media dictates, portrays, and disseminates it to the masses.

Every scar erased, every line removed, every mark of age eliminated from our skin has a reason behind it. “The Substance” essentially tells the story behind those alterations on our faces and bodies. It portrays what it’s like especially for women as the standards are undeniably harsher on us—more particular, more exacting—since from the onset, the media’s male gaze designated women into roles of being merely looked at.

Perhaps the point of today’s feminism is that we all have a choice now, a chance, a say in our personal and political matters. So if a woman chooses to have her body altered, then so be it…But more than the result of such changes, what about what made her feel lacking in the first place? The impossibly high standards that made her resort to having parts of herself removed?

The film doesn’t tell us in a black-and-white way that it’s wrong to have parts of ourselves change in order to fit society’s standards or, more importantly for celebrities and those with front-facing jobs in the media, to keep doing what they love. Instead, it shows us why we would want to have to change in the first place. Because perhaps the wrong is not in the ends nor the means but in the reason behind them—the ultimatums that pushed us, the pressure that caused the decision to change ourselves.

The Subjectivity of Being Objectified

With the film’s narrative primarily hinged on the concept of beauty, it is impossible that it shouldn’t exhibit a focal point on appearances. And yet, in spite of the zoom-ins on women’s bodies, the slow tilts and pans across certain parts, and the obvious eye for movement and exposure of as much of the body as possible, “The Substance” achieves a level of subjectivity within and surrounding those circumstances. Indeed, we empathize with the main character’s subjectivity of being objectified.

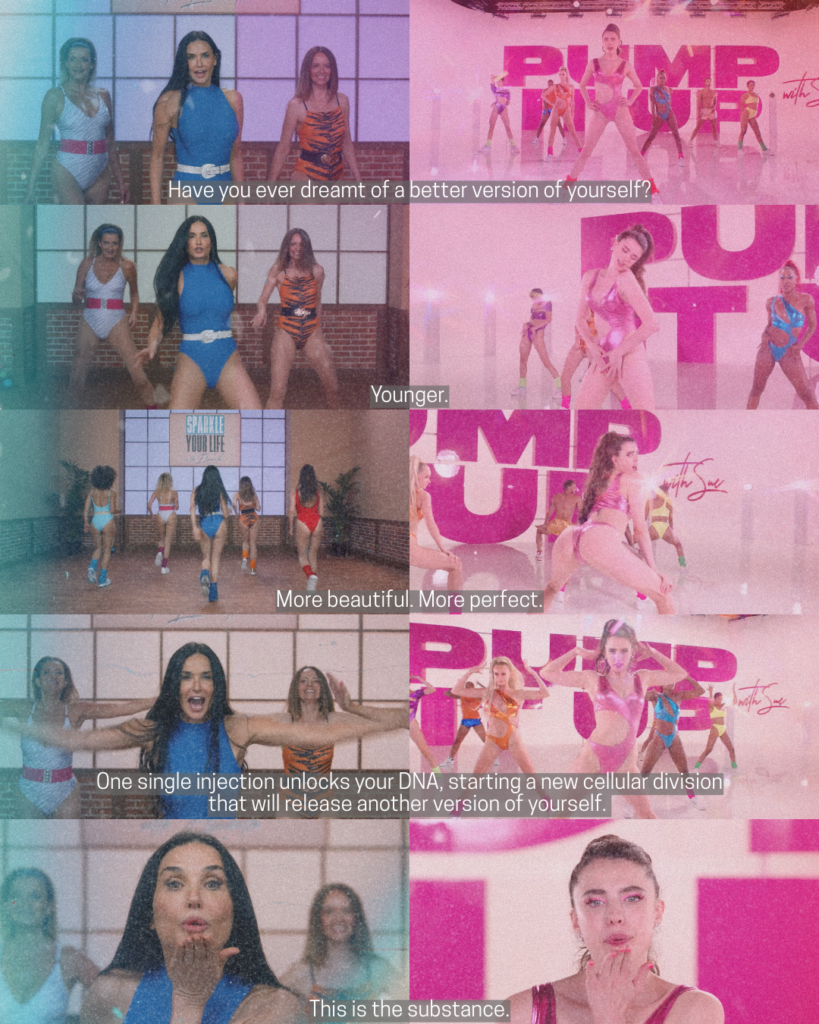

Sue blowing a kiss for the camera after her show

Considering the camera work, the film would’ve been objectifying—if not for letting us also see the big picture. And the big picture is that this is Elisabeth’s world, this is Sue’s world—this is millions of other women’s world. Living in the limelight, being constantly looked at through a lens, and having to live up to standards of beauty, popularity, status, and some other factor that the masses deem fit to be worthy of their attention. Otherwise, like Demi Moore’s Elisabeth Sparkle—who’s been a celebrity for decades when she gets fired by producers due to her age and declining appeal—they’re forced to leave the industry, or they’re altogether rejected and shunned once they no longer fit the bill.

Elisabeth blowing a kiss for the camera after her show

From the moment you start, the clock is ticking against you, and you have to do everything you can to catch up and keep holding everybody’s attention. This is yet another form of oppression and an internalized one, at that.

The film shows us the unfairness of life in the media industry—how, from the moment you start, the clock is ticking against you, and you have to do everything you can to catch up and keep holding everybody’s attention. How this is yet another form of oppression and an internalized one, at that, so that for all of Elisabeth’s desperation over something as arguably superficial as fame, the film, through the female gaze, makes us relate and empathize with her even in her ivory tower.

We see her, we understand her world. We see what she’s subject to, so we understand her decision. Even if we think it’s wrong and shallow for anybody to choose as Elisabeth did—to subject herself through the Substance to a body-altering pain so she could have a “better version” of herself in the form a younger, “more beautiful” woman—we get why she feels she has to do it, why it’s the right thing for her. And deep down, the film makes us ask ourselves, don’t we want it, too?

The Gory Behind the Glory of Beauty

At the same time, the film does not miss to remind us that undergoing those changes to our bodies is not easy. If the transformation scene—the first time Elisabeth ever takes the Substance—is anything to go by, the glory is unattainable without the gory. The film does not skip the grisly details—the bloody, spine-ripping, coma-inducing moment that eventually births Elisabeth into a new body, even a new persona altogether that she names Sue (played by Margaret Qualley).

This pursuit of beauty—in the traditional sense of it being equivalent to youth—is itself not beautiful. It’s horrific, perhaps literally and physically but also emotionally as we see in the film, where Elisabeth later becomes alienated from herself. She thinks of Sue as another, as “her”, when in fact, it’s also Elisabeth. As the voice of the Substance likes to remind Elisabeth, “You can’t escape yourself…There is no she and you. You are one.” Elisabeth starts to hate Sue, in essence hating herself: her (or Sue’s) decision to cheat the rules, to disregard the balance, to essentially have more time as her younger, “better” self so she can experience the fame and fortune that was denied her at the start of the story.

snippets and quotes from “The Substance” (Fargeat, 2024)

Inevitable Changes

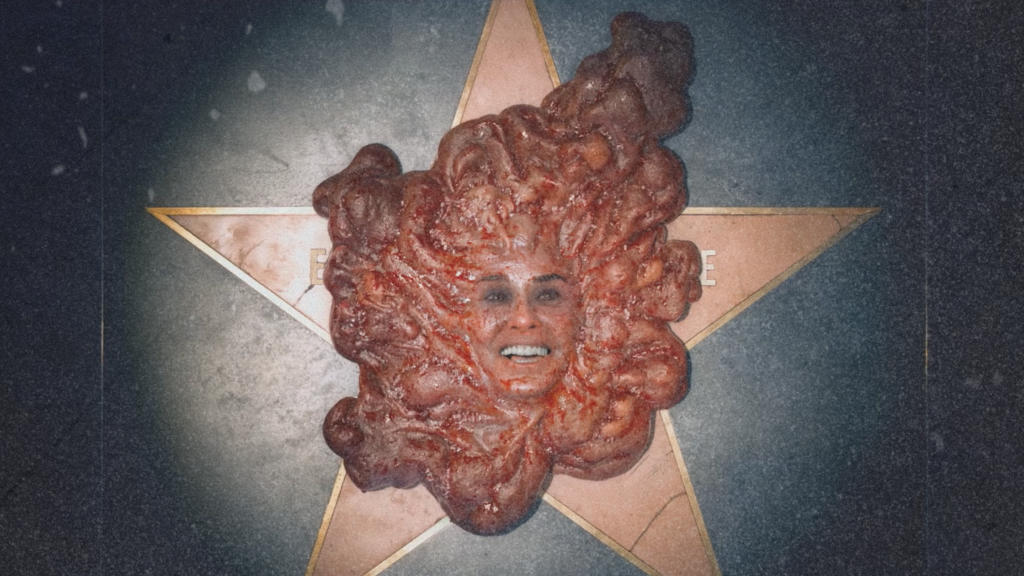

The fading of beauty—or at least the changes in it—that time brings is inevitable, no matter how much we try to avoid it, even overcome it. In the end, for all of the bargaining that she does, her skirting around the rules, it eventually catches up to Elisabeth. All the horrors she wished away from her body—the wrinkles, the sagging breasts—as well as all the things expected from her—the constant smiles, the nakedness—all catch up to Elisabeth in the film’s cinematically literal way so that she becomes one big hulk of unidentifiable monstrosities. A veritable ugliness.

In the end, having seen herself the horror that she’s become, it’s her own original face—Elisabeth’s, not Sue’s—that she plasters onto her new one to cover the ugliness up. Like she’s only now realizing that she should’ve stuck with what she had in the first place, shouldn’t have changed it. It was enough, she was beautiful.

“ElisaSue” covers herself up with a cutout of Elisabeth’s face.

She’s only now realizing that she should’ve stuck with what she had in the first place, shouldn’t have changed it. It was enough, she was beautiful.

And yet, the irony is that now, she’s exactly where she was at the start of the film—deemed ugly with an opportunity to look otherwise, look “better”, look younger. Only this time, the stakes are heightened. She’s not merely old but still attractive like she was when she was fired. This time, the film made it a point to turn Elisabeth into something truly, disgustingly ugly. And she chooses to do the same: to go back to being young instead of showing up as hideously unattractive. Only this time, her definition of “young” is ironically the version of her face when she was deemed too “old” to be beautiful. So she, as this new monster, dons a mask—a cutout of her old face as Elisabeth—and goes out into the world once again.

Throwing Out (and Throwing Up) Internalized One-Dimensional Ideals of Beauty

Her desire to change in order to keep her status—to keep doing what she loves—is not her fault. Sure, we cannot—should not—completely disregard the significance of self-awareness in overcoming one’s current state, but in the first place, she should not have been made to change, to even feel like she needed to.

Eventually, the mask falls off, and people see Elisabeth for what she’s become. She is unrecognizable, unadmirable—a horror irredeemable by any kind of procedure or Substance. A paradox in itself wherein she only ever did what was needed to become what people demanded of her—took the Substance, cheated her way through it so she could continue being beautiful for their sake—and yet in the process of doing so, the people nonetheless shun her for what she’s turned out to be.

And so, she throws up at them because she’s finally had enough of the hypocrisy, the oppression, the impossible, never-ending need to live up to people’s standards. And it’s when she realizes this and unleashes herself upon them—in the film’s usual literalness, this time in the symbolic visual of Elisabeth vomiting all over the audience—that the narrative reaches a satisfaction for Elisabeth’s character. It’s what she should’ve done in the very first place—to reject their claims on her body and what she gets to do with it and when; to throw up the media and society’s ideals of beauty that she’s been fed and forced to swallow, to choke on in all her life as a star.

As is the nature of the female gaze, we don’t blame Elisabeth. Instead, we’re made to see through to the bottom line and realize that her desire to change in order to keep her status—to keep doing what she loves—is not her fault. Sure, we cannot—should not—completely disregard the significance of self-awareness in overcoming one’s current state, but in the first place, she should not have been made to change, to even feel like she needed to. It’s the system that women like her are in—a system on which our own media and reality is built—that needs change.

Empowerment at the Last Minute

While the film may have granted Elisabeth’s character the subjectivity she deserves, and she gets the means to attain her desire through the Substance, using it according to her will—thus portraying a strong female character with her own mind to do things, her own agency—the empowerment factor of the female gaze is a little harder to find in the cinematic narrative.

The film does not show us a woman who actively goes against the status quo or fights for other people’s rights on the matter. In fact, up to the point where Elisabeth’s mask falls off, she goes by their very same set of rules and ideals on beauty, hence her desire to be Sue most, if not all, of the time. Until the moment that Elisabeth throws up at the audience, defies society, then claims her spot as a star despite her ugliness, her character does nothing to fight these oppressive rulings on people’s bodies.

Elisabeth sitting in front of a poster of herself as she learns about the Substance

Though perhaps there lies the point of the film: that for stars like Elisabeth, the challenge of internalized beauty standards is greater, especially when their work of being onscreen requires certain aesthetics. The film empowers her—allows her a shift in role from being an object of people’s standards to being a subject with her own right—only at the last second, where Elisabeth is finally at peace with herself.

In the closing scene, Elisabeth has her original face even if she’s nothing else now but a mass of blood and gore. It’s taken her all this time to know that her face—original, untouched, unaltered—is all she’s ever needed. And yet, even in her dying breath, even in the mishmash of things she’s become, the parts of herself—both hated and revered—that have morphed into one, the changes having caught up to her, she still crawls back to stardom because it is what she knows and loves. It is what she dreams, and in the end, however twisted, she gets an approximation of that dream when the golden sparks of stardom shower upon her face that is all that she has left to show for it.

Elisabeth Sparkle is a star.

Empowering by Asking

It’s in this ending, however, that we realize that for all the rationality, the justification we put to things like the Substance—and in our reality, procedures like cosmetic surgeries—they still present problems, from the deep-down personal image we have of ourselves, of beauty, to the wider societal implications on the diversity of identity, ethnicity, and age. How these things establish a hierarchy, preserve a duality that one is beautiful only by exact standards, otherwise it’s ugly; that one is superior if it meets certain criteria, otherwise it’s inferior.

Perhaps a lot of the film’s empowerment comes in the form of a question—or several—that it leaves the audience to ponder. The Substance, symbolic of our own real world’s body-altering procedures, gives us an easy out instead of dealing with the deeper problem. Indeed, it makes it easier for the status quo on beauty to live on—and why shouldn’t it? Slim, sexy, young. Unblemished, sweet, and pleasant, among other things. It’s what we’ve always known. It’s easy, comfortable, bearable to have just one kind of look be the definition of beauty. But if we were all to become beautiful—across all ages, in every one of our shapes, sizes, and looks—would there even be such a thing as beauty? Or does being beautiful always have to mean being the exception, the one above the rest?

Why should there be a hierarchy to it at all?

Sources

Fargeat, C. (Director). (2024). The Substance [Film].

Research and Markets. (2025 February 10). Cosmetic Surgery Market Forecast Report 2025-2033, by Procedure, Gender, Age Group, End User and Region. Globe Newswire. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2025/02/10/3023333/28124/en/Cosmetic-Surgery-Market-Forecast-Report-2025-2033-by-Procedure-Gender-Age-Group-End-User-and-Region.html

Statista Research Department. (2025 February 18). Cosmetic surgery – Statistics & Facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/3734/cosmetic-surgery/#topicOverview

Zochowski Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. (n.d.). The Most Popular Cosmetic Procedures by Age. https://www.zochowskiplasticsurgery.com/the-most-popular-cosmetic-procedures-by-age

Read Next

We all know how painful and unpleasant menstruating can be, so why not feel as good about it as we can while we’re…

Why are we so against growing old—looking old? When we think of beauty, we think of someone young. Snow White wasn't old when…

The Muse Inks

© 2025 The Muse Inks. All Rights Reserved.