The Muse Inks

Introducing the Female Gaze through "Babae at Baril" (2019)

by Gabrielle Lopez

March 25, 2025

Content Warning: This article contains a review of a film that includes scenes of sexual assault and violence. Some plot spoilers are also included. Reader discretion is advised.

We’ve all seen it. There’s a woman onscreen. Cue a zoom-in on her dolled-up face. Transition to a slow tilt up her body. Pause dramatically on certain parts.

She’s often cast in a role of stereotypical femininity—or she’s not cast at all. In the instance of female presence onscreen, the woman is only one among the many men that still dominate the space, the story. It is still the man who’s the protagonist, the center of the cinematic world, the driver of the plot while the woman is made to stand behind him.

This is the “reel life” for women—and it often translates into our real life, too. In turn, what we live in reality goes back into the art we make. It’s an endless cycle, or so the cinematic norm under the male gaze goes. Through the male gaze, we are made to objectify the woman and to identify with the man, to treat her as the inferior, sexualized other and him as the superior, idolized one. (Mulvey, 1975 & Jackson, 2023)

Filmmakers have challenged this norm, for instance through the Bechdel Test that supposedly serves as a benchmark for the improvement in women’s portrayal. We can identify the positive change if 1) there are at least two women featured, 2) they talk to one another, and 3) they talk specifically about other things other than a man.

But is that all that it takes for us to say that women are now respectfully and realistically portrayed?

Let’s go back to the problem, the status quo: the male gaze.

What if there was a female gaze instead?

What is the Female Gaze?

If not simply putting women into more roles, what is the female gaze? What is it beyond what we know from popular culture—strong female characters, women who have more to do in their lives than talk about men, the strong independent type, the modern woman who can do it all?

In my study on the female gaze as a feminist cinematic language, I started with the question, “What does it mean to be a woman?” Recognizing the mis- and underrepresentation of women in film—how these influence the treatment of women in real life—that question turned into, “How can there be more to being a woman?”. (Lopez, 2024)

The importance of film in shaping realities turns to the female gaze for an answer.

challenging the Bechdel Test in “Babae at Baril” (Red, 2019): two women talking about a man’s abusive treatment of them

In general, “the female gaze is a means of representation that highlights the woman as an empowered and empowering subject (as opposed to being a sexualized object). It presents narratives with subjectivity and empathy to women’s experiences.”

My study used Soloway’s (2016) definition as a ground for the female gaze, redefining it in more specific terms—subjectivity, agency, and empowerment. Under these three, other definitions from similar studies I’ve researched fall in as indicators.

To see this definition applied, we look at the Filipino film directed by Rae Red, “Babae at Baril” (2019), a cinematic piece that blends action, crime, suspense, and drama with the turmoil of Filipino class society, the reality of pervading violence, and women’s experiences within that system. The story revolves around Babae, a woman who is symbolically left unnamed in the film to stand for any and every woman. She experiences various instances of gender-based discrimination and harassment, so when she finds a gun, she uses it against the men who mistreat her. A classic tale under the rape-revenge genre told in such a way that resonates with the everyday Filipina.

Subjectivity

By seeing the woman—or any character—through a female gaze, we feel with her in her situation. Emotions and experiences are the focal point instead of appearances. Where the male gaze objectifies, the female gaze empathizes.

Where we might see a woman idealized and sexualized for her “virtues” and beauty through the male gaze, we go beyond what’s skin-deep and get to know her more through the female gaze. Who is she? Where does she come from? Why is she in this situation?

Rae Red’s “Babae at Baril” pays attention to these questions right from the opening scene, where we learn about Babae’s situation at work and in life. Throughout the film, we see how Babae changes, especially from the moment that the girl gets the gun. In my analysis of the film for my study on the female gaze, subjectivity is defined as having a presence of complex, flawed characters. (Lopez, 2024)

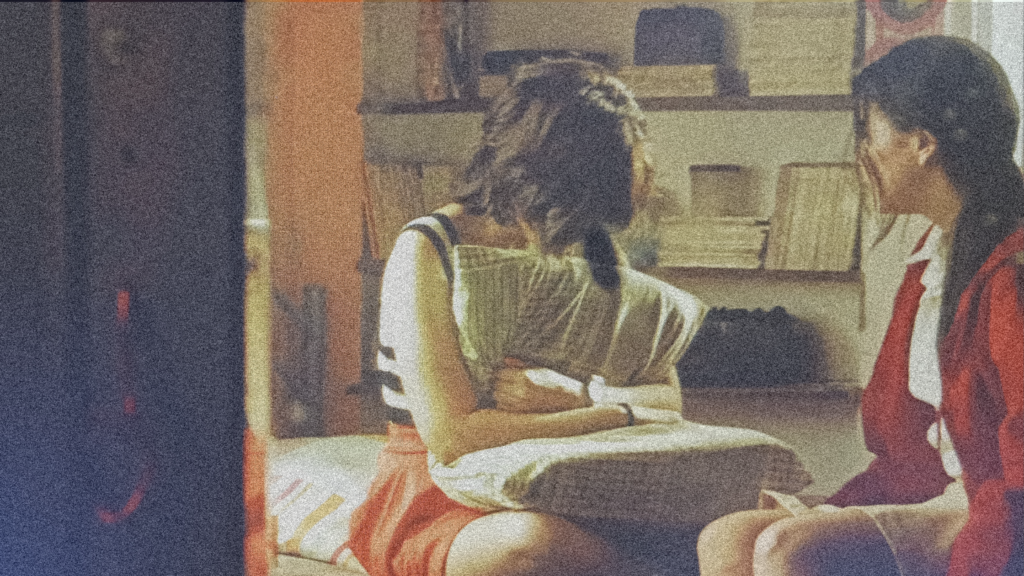

snippets from the opening scenes of “Babae at Baril” (Red, 2019)

Since we’re looking into how films can be feminist, we cannot ignore feminist issues. Subjectivity through the female gaze means a portrayal of women’s experiences of gender-based oppressions. “Babae at Baril” clearly shows these in more ways than one, both in public and private spheres of everyday living. From Babae being catcalled in the streets to being disrespected by ignorant men, from facing domestic harassment to being assaulted at work, the film ultimately shows that oppression can happen anywhere, any time, and not just in one given space with exception to certain women, though we cannot deny that some have more means to protect themselves from acts of discrimination than others. The female gaze does not neglect this part of women’s reality; instead, it weaves it into the narrative and deals with it.

In Babae’s case, she learns to fight back, but even in doing so—even when her actions with the gun take a wrong turn—she is not objectified, glorified, or romanticized. Neither is she blamed for being a victim in the first place. Subjectivity is defined by this third aspect—of having a focus on characters’ actions and their consequences instead of only their appearances.

Oppression can happen anywhere, any time, and not just in one given space with exception to certain women…The female gaze does not neglect this part of women’s reality; instead, it weaves it into the narrative and deals with it.

Agency

Subjectivity goes on to give the woman agency, which is the power to do something about her situation, to make changes, and essentially to get the story rolling. Through the female gaze, the woman becomes the writer of her own story.

Where the female gaze turned her into a real person from being a doll—a mere face and body to be looked at—now it gives her the ability to act, to decide for herself. Beyond asking “Who is she?”, the female gaze poses and answers the question, “What will she do?”.

The woman’s choices and their consequences are relevant to her development as an individual and to the development of the cinematic world she inhabits. Through agency, she is not only one but a part of a whole. She is not only “her”—an individual, a person. Instead, she is one of “them”—women, a collective, a community, a society.

Take Babae for example. The moment she picked up the gun, she picks up her own rage and courage to fight back. After experiencing multiple oppressions, she decides that she’s had enough, and she will no longer stand by and take them quietly. This is the first half of agency through the female gaze: the power of a character as an individual, recognizing and overcoming their flaws. Babae realizes her own passivity and now becomes vocal—and in the theme of the film, violent—about the wrongs done against her.

Babae fights back and stands up for herself.

More than that, agency is also the power given to the woman, this time as a part of society. The female gaze shows that her actions do not affect only her but others, too. In the film, we see this in a few scenes, where Babae concerns herself with her roommate, a fellow woman, who is sexually harassed and abused by her boyfriend. At a pivotal point in the story, Babae stands up for her friend and defends her against more abuse; she does not hesitate to protect her friend. In one of the latter scenes, Babae decides to actively pursue and fight the abusive boyfriend. When her friend asked what she planned to do, Babae only said,

“Ako na bahala.”

For once, the woman’s fate is not placed in a man’s hands. In saying those words, Rae Red not only cast the woman as a protagonist but an active one at that. A woman who has the means and the will to do something. A woman who can decide her course for herself and act of her own volition.

While Babae may have gained agency the moment she gained the gun, she does not lose it, either, the moment she throws it into the river at the end scene. In fact, this act is yet another manifestation of her agency—that she is able to step out of the cycle of violence, the patriarchal norm. Though the narrative ends there as the credits roll with one last look at her in an emotional state—with her very own gaze—her keeping her agency is implied. Beyond the story, Babae can now take the next step to become something new, something other than the norms of femininity and masculinity. Having been looked at, she will now look on and redefine herself on her own terms. And so the image becomes the owner of the gaze, the doer of action.

Empowerment

“If she can do it, so can I.”

The last part of the female gaze in film is empowerment, which is essentially a transformation—a positive change in roles given to women in film. From passive to active, from images to be looked at to owners of the gaze. In empowering female characters in film, we empower the audiences, too. It prompts the thought, “If she can do it, so can I”, as viewers identify with the characters onscreen and aspire to be like them.

In “Babae at Baril”, we are taken through a journey of identifying with Babae in different circumstances. At the start, we identify with her struggles based on our common experiences of gender-based oppression. In the midpoint of the film, we relate to her rage, the urge to fight back and give our perpetrators a taste of their own treatments of us. At the height of the story, we now identify with Babae as she gives up the gun and decides that she is better than all of this. We are better than the world men have built for us.

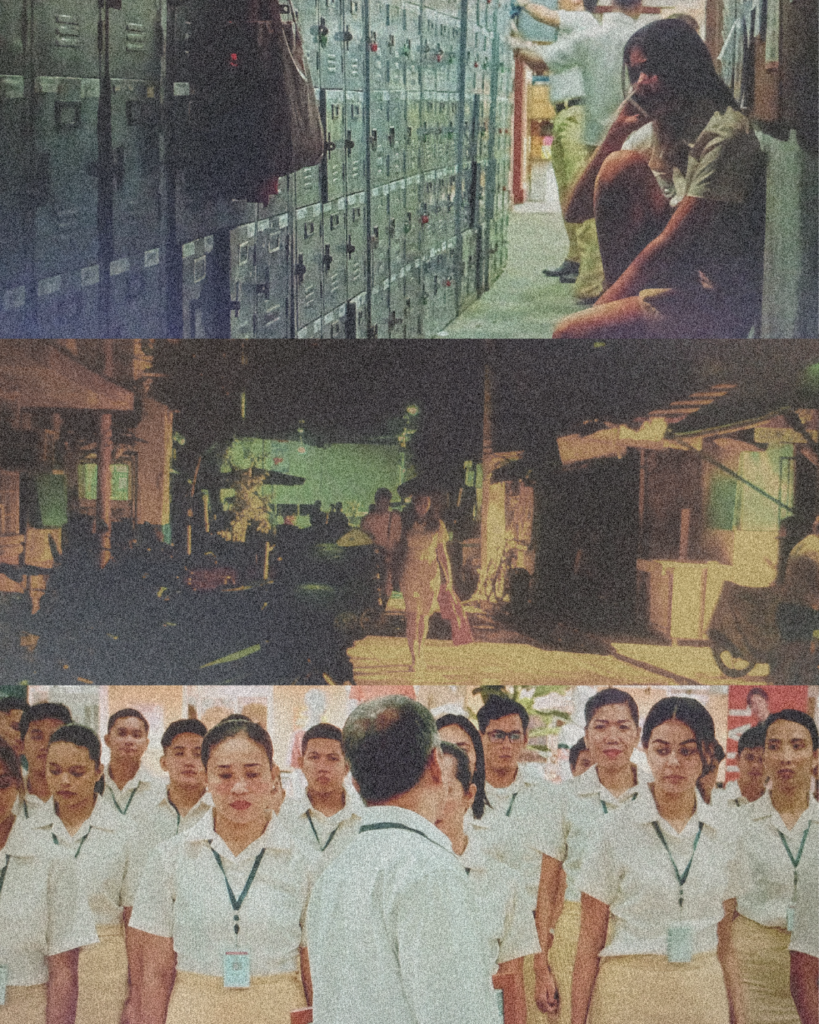

Babae’s journey from oppression to revenge to resolution.

We are better than the world men have built for us.

And at the resolution of the film, as she stands by looking on—exhausted, in despair, relieved, raging, righteous, determined to be different—we also identify with Babae in her desire to be more, to be better.

Now, she can.

And in her empowerment, we are empowered.

She gets the gun for herself and uses it to fight back as she experienced the same oppressions all over again: the catcalling, the disrespect and disregard, the domestic abuse, the workplace harassment. Babae subverts her initial role—one of passive femininity—and switches it up so that she now has the upper hand. She is no longer simply on the receiving end of men’s cruel treatment of her. She overcomes her imposed state of being an object, becoming an active figure who owns her voice and volition. To quote from my critical analysis study,

“She defied the norm that she should not be anything other than silent and submissive. She could also be ‘like men’ in their power and dominance. Though at the end of the film, she was made to give this up, it was not for the reason that women like Babae could not be ‘masculine’ but because it was simply morally wrong for her to continue the cycle of violence.”

Towards the end of the film, Babae is empowered once more through another change in roles.

She realizes that she does not have to be like men just so she wouldn’t be like the stereotype of a woman. She can be something else, something more. And though it is left undefined in the film due to the narrative constraints, it opens up a new definition of female power, of women’s role in cinema.

The Female Gaze as Feminist

So what exactly makes the female gaze effective in changing the cinematic norms of portrayal for women? How can we say that it can be truly feminist?

We go back to the male gaze—and deconstruct it.

The two parts: scopophilia (the pleasure in looking at others) and narcissism (the pleasure in self-identifying with an image). The female gaze subverts the psychoanalytic norms that make up these two—specifically, Freud’s notion of castration and Lacan’s idea of self-fulfillment through mirror images.

By being subjective to women’s deeper experiences, the female gaze topples the norm that the woman be simply sexualized and punished onscreen. By extension, in giving women the agency to act and in empowering them out of the stereotypical role of passive femininity, the female gaze defies the standard that men should be the one to look up to because they are the ones in action. This time, the woman is the one, not the other.

snippets from the final scene of “Babae at Baril” (Red, 2019): a female gaze on Babae’s varying emotions as she herself gazes on

If a film does not sexualize or punish the woman—or in the case of such stories like “Babae at Baril”, where it is a part of the narrative to show the realities of women’s oppressions, if a film at least resolves these issues—then we can say that it’s feminist.

If a film places the woman as the ideal subject instead of the stereotypical man—or the hegemonic masculine image, one that perpetuates violence—then we can say that it’s feminist.

The female gaze not only deconstructs the patriarchal status quo in cinema but constructs a new one—where female desire (including but not limited to the sexual sense of the word) is highlighted. It is not enough that the female gaze is unlike the male gaze—that the woman is not mistreated or that she is not cast aside in favor of the man. The female gaze also gives the woman the opportunity for individual interests and lets her pursue them.

Babae wanted retribution—she went after it. In the end, she got it, if not in the typical male sense of the word, where she would’ve ended up killing her perpetrator, like all the men who owned the same gun before her did. Instead, she got her revenge by proving to the men around her that their actions are beneath her, and she will not stoop to be like them. She is better than the norm of violence and oppression.

More so, the female gaze moves the woman to fight for her rights as a part of society, as one of a whole. As part of a collective that is essentially womanhood.

The female gaze asks, “What does she want? How will she get it?”.

“How does she fight for her rights as a woman—as a person?”.

And only then—in showing a story of a girl that is as loaded with these possibilities as a gun—can we say that a film is feminist.

Sources

Jackson, L.M. (2023, July 14). The Invention of “The Male Gaze”. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/books/second-read/the-invention of-the-male-gaze

Lopez, G.M.S. (2024). “Babae at Baril” (2019): A Study of the Female Gaze in Filipino Film As A Feminist Language of Desire (Undergraduate Thesis). University of Santo Tomas, Manila, Philippines.

Mulvey, L. (1975). Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Film: Psychology, Society, and Ideology, 803-816. https://www.amherst.edu/system/files/media/1021/Laura%2520Mulvey, %2520Visual%2520Pleasure.pdf

Red, R. (Director). (2019). Babae at Baril [Film].

Soloway, J. (2016, September 11). The Female Gaze. Topple Productions. https://www.toppleproductions.com/the-female-gaze/

Read Next

We all know how painful and unpleasant menstruating can be, so why not feel as good about it as we can while we’re…

Why are we so against growing old—looking old? When we think of beauty, we think of someone young. Snow White wasn't old when…

The Muse Inks

© 2025 The Muse Inks. All Rights Reserved.